The

publication of this book celebrates the first American exhibition of Fosco

Maraini ‘s photographs, held at the Tenri Gallery in New York City, April throught June of 1999.

The

publication of this book celebrates the first American exhibition of Fosco

Maraini ‘s photographs, held at the Tenri Gallery in New York City, April throught June of 1999.

The

publication of this book, as well as the exhibition and the film about Maraini,

Silently Drawn, could not have been possible without the extraordinary

assistance of many people, for many different reasons. […] John Bigelow Taylor,

Diane Dubler, April 1999

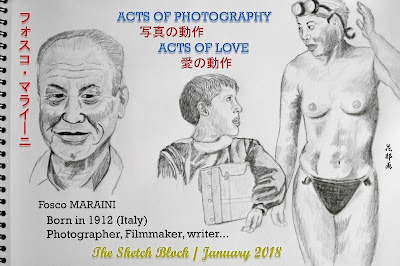

MARAINI -

Acts of Photography Acts of Love, Joost Elffers Book, 168 pages, 1999.

Maraini on Maraini

Excerpts from Bagueria

By Dacia Maraini

|

| (1912 - 2004) |

There was a

certain reserve between my father and me, something never put into words, which

left its mark on our relationship as ‘mates’ » : this had been initiated

by him as if there were no differences of age between us, as if one Saturday

morning we might together come to a decision to go for a six-hour excursion

into the mountains, or go out rowing in the sun for four hours, or for an

hour’s swim in the icy cold water of the river.

A warning should

have been enough and sometimes it was. But even when I imagined my strength to

be greater than it was, I would fling myself forward and do my best to keep up

with him. Once my mother gave him a slap. He did not return it. He had brought

me back from a trip into the mountains, which had lasted seven hours in the

frost, and I had a high temperature and lips that had turned violet, and my

feet were quite frozen.

But another

time I saved his life. He had to leave early in the morning for a trip into the

mountains with some friends. I was ill, I seemed to be delirious. He told his

friends to go ahead and he would join them the next day. They went off and were

swept away by an avalanche and were all killed.

Between us

there was above all a sense of solidarity, a comradeship, a bold independence,

an exciting defiance of rules of ordinary common sense. Like two travelling

companions, two sportsmen, two friends for life, we could communicate with each

other by a look. Words got in the way, and in fact we spoke little. With me he

laughed, played, ran. We were earnest explorers and we got to know the tracks

in the middle of the forest. We paddled up the rivers, we faced the perils of

the sea but he did not speak; lest words create something limiting and commonplace

– at least, if they were spoken out loud; only thought was considered ‘noble’.

Indeed he wrote, just as his mother used to write – my grandmother, the very

beautiful Yoi, half English and half Polish, with whom so many men of her time

had fallen in love. It was acceptable to write rather than to talk. This was

the silent commandment, never articulated, that was in force between us. I

obeyed the rules. But how was I to make use

of the love I felt? To write what?

My father’s

books are those of a scientist and he never ceased to write about ethnology, a

science poised between the humanism of antiquity and new technology, which he

loved more than anything else, a way of writing that consists of observation

and analysis and at the same time is both invention and narration. But I chose

pure story telling, beyond any scientific pretensions unless it was the science

of writing itself. I began by writing poetry that was all about him. And then,

with a struggle, my gaze shifted to other faces, other smells, the backs of

other necks, other smiles. But with what reluctance! Almost as if the world

consisted only of his swaying yet resolute walk, his embarrassed cough, his

departure at dawn for a distant future, far away and unknown yet absolutely

wonderful.

[…] I never

asked my father anything about writing. It seemed to me that his mere presence,

sitting at the table with his back facing the door (which he always insisted

must be kept shut), his obstinate insistence on silence, was itself an

affirmation of his seriousness and professional discipline.

[…] He was

forever on his travels, forever far away. I transformed my longing into an

intricate, airy architecture, into the mirage of a city and the desire to dream

with open eyes. Whenever he came back from one of his journeys I took

meticulous note of the smells he brought back with him, the smell of apples

(why does the inside of haversacks always have strong, musty underlying smell

of apples?), of dirty washing, of hair warmed by the sun, of crumpled books,

dry bread, old shoes, withered flowers, tobacco, and tiger balsam against

rheumatism. […]

Drawings : Catherine Pulleiro

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire